| How Can You Destroy a Person's Life and Only Get a Slap on the Wrist? | December 4, 2021 |

|---|---|

| By The Editorial Board | |

|

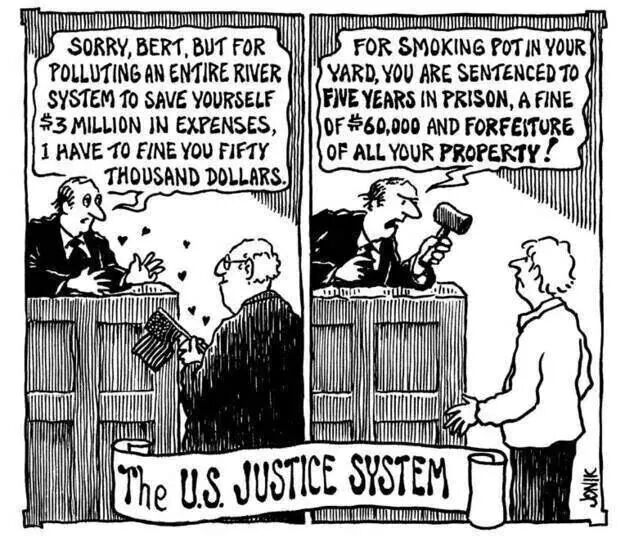

Prosecutors are among the most powerful players in the criminal justice system. They can send a defendant off to years in prison, or even to death row. Most wield this power honorably. Yet, when prosecutors don't, they rarely pay a price, even for repeated and egregious misconduct that puts innocent people behind bars.

Why? Because they are protected by layers of silence and secrecy that are written into local, state and federal policy, shielding them from any real accountability for wrongdoing. New York City offers a prime example of a problem endemic to the nation. Consider the city's official reaction to the barrelful of misconduct in Queens that a group of law professors recently brought to light. As The Times reported last month, the professors filed grievances against 21 prosecutors in the borough - for everything from lying in open court to withholding key evidence from the defense - and then posted those grievances to a public website. These weren't close calls. In every instance an appeals court had made a finding of prosecutorial misconduct; in many cases the misconduct was so severe that it required overturning a guilty verdict and releasing someone from prison. Three men wrongfully convicted of a 1996 murder were exonerated after 24 years behind bars. But that rectified only the most glaring injustice. To date, none of the prosecutors have faced any public consequences. Some are still working. How did the city respond to this litany of widespread misconduct by its own agents? It went after the professors who publicized it. In a letter to the committee that handles misconduct charges, New York City's top lawyer, known as the corporation counsel, accused the professors of abusing the grievance process "to promote a political agenda" and of violating a state law that requires formal complaints about lawyers' conduct to be kept secret unless judicial authorities decide otherwise. (They virtually never do.) The grievance committee agreed to punish the professors by denying them access to any future updates on their complaints - even though state law requires that complainants be kept informed throughout the process. The upshot is that the committee could dismiss the complaints tomorrow and no one would know. For good measure, the corporation counsel then sought to keep secret the letter requesting the professors be punished for violating the secrecy law. This isn't just shooting the messenger; it's tossing the gun into the East River and threatening anyone who tries to fish it out. We know about all this because the professors sued the city in federal court, claiming that the secrecy law infringes on the First Amendment. How could it not? If someone tells a Times reporter about a prosecutor's misconduct, the reporter is free to write a story addressing those allegations for all the world to see. But if the same person files a formal grievance about the same misconduct with the state, she's barred from talking about it. It's not even clear what the punishment for violating the law would be - as evidenced by the fact that dozens of prominent lawyers, including former New York judges and even prosecutors, went public with grievances they filed against Rudy Giuliani over his role in Donald Trump's efforts to subvert the 2020 election and encourage the Jan. 6 riot at the Capitol. To date, none of these lawyers have faced public sanctions for speaking to the press. In theory, the secrecy law exists to protect lawyers from being smeared by frivolous complaints, but that rationale makes no sense when applied to prosecutors, who are public officials doing the state's work. In the Queens cases, their misconduct is already a matter of public record. Even if it weren't, there is no principled reason to prevent the public airing of complaints - not to mention public hearings - against officials who have the power to send people to prison. Certainly the defendants they face off against in court don't enjoy such privileges. New York shelters its lawyers from disciplinary measures more than most states in the country, even as it ranks near the top in total number of exonerations - a majority of which are the result of misconduct by prosecutors. Meanwhile, the few attempts to increase oversight of New York prosecutors have been stymied. A 2018 law established a commission specifically to deal with prosecutorial misconduct in a more independent and transparent way. But the state district attorneys' association challenged it and a court struck it down as unconstitutional. Lawmakers designed a new commission this year, but it appears that no commissioners have yet been appointed to it.

New York's prosecutor-protection racket is, alas, far from unique. In Washington, the Justice Department aggressively shields its own prosecutors from outside accountability thanks to a 1988 law that lets the agency essentially police itself. All other federal agencies - and even parts of the Justice Department, like the F.B.I. and the Drug Enforcement Administration - are subject to oversight by independent inspectors general, who conduct thorough investigations and issue lengthy reports with their findings. Federal prosecutors skate by on an internal review process that is run out of the Office of Professional Responsibility, whose head is appointed by, and reports directly to, the attorney general. The office almost never makes its findings public, and when it does it often provides only a brief summary months after the fact. In the words of one legal-ethics expert, it's a "black hole." (By contrast, the inspector general's office of the Justice Department just released its semiannual report, as it is required to do by law, detailing the 52 reports it issued between April and September of this year, as well as the closing of investigations that resulted in 68 convictions or guilty pleas and 66 firings, resignations or disciplinary actions.) The level of scrutiny that federal prosecutors are subject to matters so much because they are just as prone to misconduct as their state and local counterparts. Take the botched prosecution of former Senator Ted Stevens of Alaska on corruption charges, or the legal green light Justice Department lawyers gave interrogators to torture terrorism suspects, or the more recent revelation that Jeffrey Epstein, the sexual predator, got a sweetheart deal in 2008 from his prosecutor, Alex Acosta, who later became labor secretary in the Trump administration. Yet in the latter two cases, the Office of Professional Responsibility found no misconduct. Mr. Acosta was guilty only of "poor judgment," the office said. In the Stevens case, the office found misconduct but said it was unintentional, and it let the prosecutors off with a slap on the wrist. Have there been other similarly egregious failures to hold prosecutors to account? Almost certainly. But we don't know because the Justice Department doesn't tell us. There is no principled reason for federal prosecutors to avoid the accountability expected of all public servants. Their exemption from the general rule was adopted in 1988 as a favor to Dick Thornburgh, who was then the attorney general and had tried to derail the creation of an inspector general for the Justice Department. Years later, Mr. Thornburgh admitted he had been wrong. "This is a highly professional operation that goes where the evidence leads and is not directed by the way the political winds are blowing," he said at a gathering marking the law's 25th anniversary in 2014. "I've come to be a true believer." So have large numbers of Republicans and Democrats in Congress, a remarkable fact at a moment when the parties can't agree on the time of day. Their fix is straightforward: Eliminate the loophole in the 1988 law and empower the inspector general to review claims against federal prosecutors, just as the office currently does in cases involving other Justice Department employees. A Senate bill co-sponsored by Mike Lee, Republican of Utah, and Dick Durbin, Democrat of Illinois, would do exactly this. Yet Attorney General Merrick Garland is continuing in the tradition of his predecessors by opposing any change to the existing system. Prosecutors can work in the interests of fairness and justice, but they can also cheat and destroy people's lives. They should be held accountable when they do - both to vindicate their victims and to help ensure that they can't do it again. The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We'd like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here's our email: letters@nytimes.com. |

|

Send comments to:

hjw2001@gmail.com

hjw2001@gmail.com

|